Traduction expresse: G.M.

The Need for Objective Measures of Stress in Autism

- 1CNRS, LaPSCo, Stress Physiologique et Psychosocial, Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France

- 2CNRS, LMBP, Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France

- 3Preventive and Occupational Medicine, University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand (CHU), Clermont-Ferrand, France

- 4Faculty of Health, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Physiological and Psychological Impact of Stressors

En

dépit de nombreuses définitions du stress, la signification du stress

pourrait se référer aux réponses comportementales ou mentales adaptées

qui permettent de remédier aux conséquences habituelles des facteurs de

stress liés à la vie quotidienne, comme une attention accrue à

l'accomplissement d'une tâche mentalement exigeante. Le stress peut être réel ou perçu, agréable ou désagréable (Woda et al., 2016).

Une adaptation permanente aux facteurs de stress quotidiens normaux est nécessaire, via le système de stress physiologique. La réponse au stress physiologique déclenche des adaptations métaboliques aux facteurs de stress aigus (par activation du système nerveux autonome résultant principalement de la libération de l'épinéphrine par la médula surrénale) et anticipe ce qui peut arriver (par activation de l'axe surrénal hypothalamo-hypophysaire entraînant la libération de corticostéroïdes.

Des conséquences morbides peuvent être attendues lorsqu'un individu est affecté par une défaillance du système de réponse au stress aux facteurs de stress. Par conséquent, dans son lieu ordinaire, le terme «stress» est souvent considéré comme un concept négatif, avec des conséquences morbides (Woda et al., 2016). L'un de ces effets négatifs est l'anxiété. Avec l'anxiété, la peur surmonte toutes les émotions et s'accompagne d'une inquiétude et d'une appréhension (Sylvers et al., 2011; Adhikari, 2014). Bien qu'il existe un chevauchement définitif entre le stress et l'anxiété, nous utiliserons le terme stress comme un impact physiologique et psychologique négatif des facteurs de stress.

Despite the numerous definition of stress, the meaning of stress could refer to the adaptive behavioral or mental responses willing to address the common life consequences of stressors, such as increased attention to perform a mentally demanding task. The stressor can be real or perceived, pleasant, or unpleasant (Woda et al., 2016). Permanent adaptation to normal daily stressors is needed, via the physiological stress system. The physiological stress response triggers metabolic adaptations to the acute stressors (via activation of the autonomic nervous system mostly resulting in release of epinephrine by the adrenal medulla) and anticipates what may happen (via activation of the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis resulting in release of corticosteroids by the cortical medulla) (McEwen, 2000; Woda et al., 2016). Morbid consequences can be expected when an individual is affected by a failure of the stress response system to stressors. Therefore, in its commonplace, the term “stress” is often viewed as a negative concept, with morbid consequences (Woda et al., 2016). One of these negative effects is anxiety. With anxiety, fear overcomes all emotions and is accompanied by worry and apprehension (Sylvers et al., 2011; Adhikari, 2014). While there is a definite overlap between stress and anxiety, we will use the term stress as a negative physiological and psychological impact of stressors.

Une adaptation permanente aux facteurs de stress quotidiens normaux est nécessaire, via le système de stress physiologique. La réponse au stress physiologique déclenche des adaptations métaboliques aux facteurs de stress aigus (par activation du système nerveux autonome résultant principalement de la libération de l'épinéphrine par la médula surrénale) et anticipe ce qui peut arriver (par activation de l'axe surrénal hypothalamo-hypophysaire entraînant la libération de corticostéroïdes.

Des conséquences morbides peuvent être attendues lorsqu'un individu est affecté par une défaillance du système de réponse au stress aux facteurs de stress. Par conséquent, dans son lieu ordinaire, le terme «stress» est souvent considéré comme un concept négatif, avec des conséquences morbides (Woda et al., 2016). L'un de ces effets négatifs est l'anxiété. Avec l'anxiété, la peur surmonte toutes les émotions et s'accompagne d'une inquiétude et d'une appréhension (Sylvers et al., 2011; Adhikari, 2014). Bien qu'il existe un chevauchement définitif entre le stress et l'anxiété, nous utiliserons le terme stress comme un impact physiologique et psychologique négatif des facteurs de stress.

Despite the numerous definition of stress, the meaning of stress could refer to the adaptive behavioral or mental responses willing to address the common life consequences of stressors, such as increased attention to perform a mentally demanding task. The stressor can be real or perceived, pleasant, or unpleasant (Woda et al., 2016). Permanent adaptation to normal daily stressors is needed, via the physiological stress system. The physiological stress response triggers metabolic adaptations to the acute stressors (via activation of the autonomic nervous system mostly resulting in release of epinephrine by the adrenal medulla) and anticipates what may happen (via activation of the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis resulting in release of corticosteroids by the cortical medulla) (McEwen, 2000; Woda et al., 2016). Morbid consequences can be expected when an individual is affected by a failure of the stress response system to stressors. Therefore, in its commonplace, the term “stress” is often viewed as a negative concept, with morbid consequences (Woda et al., 2016). One of these negative effects is anxiety. With anxiety, fear overcomes all emotions and is accompanied by worry and apprehension (Sylvers et al., 2011; Adhikari, 2014). While there is a definite overlap between stress and anxiety, we will use the term stress as a negative physiological and psychological impact of stressors.

Stress in Autism

Les

personnes avec un diagnostic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme ont souvent des

difficultés dans la communication et l'interaction sociale résultant du

traitement de l'information atypique et des anomalies de l'intégration

sensorielle. Cela

provoque un état de surcharge cognitive et émotionnelle associée à un

stress accru, par l'implication du système nerveux autonome, qui peut

conduire à l'apparition d'un comportement social inapproprié. Cependant,

dans la plupart des publications réelles (Reaven et al., 2012; Corbett

et al., 2016; Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2017), le stress des personnes

atteintes de troubles du spectre autistique est évalué par des

questionnaires ou parfois par des biomarqueurs de salive. Malgré

le manque de cohérence entre les scores aux questionnaires et les

niveaux de biomarqueurs de la salive (Corbett et al., 2009; Spratt et

al., 2012), ils n'y a pas d'évaluation directe et continue. Cela

suppose que les soignants ou les personnes avec un diagnotic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme puissent

reconnaître les symptômes externes et internes du stress, mais aussi

que le stress déclenche systématiquement une réponse comportementale

identifiable ou observable. Nous croyons que l'évaluation du stress ne doit pas être subjective. Les individus personnes avec un diagnotic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme devraient

bénéficier de mesures objectives continues du stress, en particulier en

sachant que près de la moitié des personnes avec un diagnotic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme n'ont

pas accès à une communication efficace pour exprimer ce stress intérieur

People with autism spectrum disorder often have difficulties in communication and social interaction resulting from atypical information processing and abnormalities in sensory integration. This causes a cognitive and emotional overload state associated with an increased stress, by the involvement of the autonomic nervous system, that can lead to the appearance of inappropriate social behavior. However, in most actual publications (Reaven et al., 2012; Corbett et al., 2016; Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2017), the stress of individuals with autism spectrum disorder is evaluated by questionnaires or sometimes by saliva biomarkers. Despite the lack of consistency between scores to questionnaires and levels of saliva biomarkers (Corbett et al., 2009; Spratt et al., 2012), they are not a direct and continuous assessment. This presupposes that caregivers or people with autism are able to recognize external and internal symptoms of stress, but also that stress systematically triggers an identifiable or observable behavioral response. We believe that stress evaluation should not be subjective. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder should benefit from objective continuous measures of stress, especially knowing that almost half of individuals with autism do not have access to effective communication to express this inner stress (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

People with autism spectrum disorder often have difficulties in communication and social interaction resulting from atypical information processing and abnormalities in sensory integration. This causes a cognitive and emotional overload state associated with an increased stress, by the involvement of the autonomic nervous system, that can lead to the appearance of inappropriate social behavior. However, in most actual publications (Reaven et al., 2012; Corbett et al., 2016; Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2017), the stress of individuals with autism spectrum disorder is evaluated by questionnaires or sometimes by saliva biomarkers. Despite the lack of consistency between scores to questionnaires and levels of saliva biomarkers (Corbett et al., 2009; Spratt et al., 2012), they are not a direct and continuous assessment. This presupposes that caregivers or people with autism are able to recognize external and internal symptoms of stress, but also that stress systematically triggers an identifiable or observable behavioral response. We believe that stress evaluation should not be subjective. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder should benefit from objective continuous measures of stress, especially knowing that almost half of individuals with autism do not have access to effective communication to express this inner stress (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Biomarkers of Stress

Aujourd'hui,

la plus grande partie de l'évaluation du stress est effectuée avec les

biomarqueurs de la salive tels que les niveaux de cortisol ou de

déshydroépiandrosterone (DHEA), ou sa forme sulfatée (DHEA-S)

(Danhof-Pont et al., 2011; Lac et al., 2012). Cependant, ces biomarqueurs ne donnent pas une évaluation directe et instantanée du stress ou de l'anxiété. Ils doivent être transportés dans un endroit frais pour l'évaluation dans un laboratoire dédié. Les

niveaux de ces biomarqueurs reflètent un niveau de stress qui peut

varier de quelques minutes à plusieurs heures, en fonction de leur

demi-vie. Par exemple, le cortisol a une demi-vie courte de 20 min, et peut ainsi révéler un stress aigu; Alors

que DHEA-S a une longue demi-vie de 16 h et révèle ainsi le stress

global d'une longue période (demi-journée) (Woda et al., 2016). En

outre, les niveaux de DHEA-S nécessiteront une longue période de temps

(plusieurs demi-vie) pour revenir aux valeurs basales. Par conséquent, DHEA-S est un biomarqueur du stress chronique. En outre, les biomarqueurs putatifs du stress qui nécessitent un échantillon de sang sont exclus en raison de la faisabilité. Même

si nous ne considérons pas le coût élevé de ces biomarqueurs, ils ont

également un manque de spécificité et des résultats contradictoires sont

rapportés (Oliveira et al., 2013; Fancourt et al., 2015; Hawn et al.,

2015; Qi et al., 2016).

Today most of stress assessment is done with saliva biomarkers such as cortisol or dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, or its sulfated form (DHEA-S) (Danhof-Pont et al., 2011; Lac et al., 2012). However, those biomarkers do not give a direct and instantaneous assessment of stress or anxiety. They need to be transported in a cool storage for assessment in a dedicated laboratory. The levels of those biomarkers reflect a level of stress which may vary from some minutes ago to several hours ago, depending on their half-life. For example cortisol has a short half-life of 20 min, and thus may reveal acute stress; whereas DHEA-S has a long half-life of 16 h and thus reveals the global stress of a long period (half a day) (Woda et al., 2016). Moreover, DHEA-S levels will need a long period of time (several half-life) to return to basal values. Therefore, DHEA-S is a biomarker of chronic stress. Besides, putative biomarkers of stress which need blood sample are excluded because of feasibility. Even if we do not consider the high cost of those biomarkers, they also lack of specificity and conflicting results are reported (Oliveira et al., 2013; Fancourt et al., 2015; Hawn et al., 2015; Qi et al., 2016).

Today most of stress assessment is done with saliva biomarkers such as cortisol or dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, or its sulfated form (DHEA-S) (Danhof-Pont et al., 2011; Lac et al., 2012). However, those biomarkers do not give a direct and instantaneous assessment of stress or anxiety. They need to be transported in a cool storage for assessment in a dedicated laboratory. The levels of those biomarkers reflect a level of stress which may vary from some minutes ago to several hours ago, depending on their half-life. For example cortisol has a short half-life of 20 min, and thus may reveal acute stress; whereas DHEA-S has a long half-life of 16 h and thus reveals the global stress of a long period (half a day) (Woda et al., 2016). Moreover, DHEA-S levels will need a long period of time (several half-life) to return to basal values. Therefore, DHEA-S is a biomarker of chronic stress. Besides, putative biomarkers of stress which need blood sample are excluded because of feasibility. Even if we do not consider the high cost of those biomarkers, they also lack of specificity and conflicting results are reported (Oliveira et al., 2013; Fancourt et al., 2015; Hawn et al., 2015; Qi et al., 2016).

The Need for a Continuous Monitoring of Stress

La détection en temps réel du stress nécessite une surveillance continue. Pour évaluer le stress dans la vie quotidienne, nous avons également besoin d'un appareil portable. Ces dispositifs doivent être non invasifs et sans douleur. Pour ces raisons, tous les marqueurs historiques du stress mesurés dans le sang, la salive ou l'urine sont exclus. La

nécessité de s'adapter aux événements externes et internes implique

l'activation du système nerveux autonome, qui est un équilibre entre

l'activité sympathique et parasympathique (Shaffer et al., 2014). Le

réflexe vagal est considéré comme une mesure de l'activité

parasympathique qui contrôle l'état de repos des organes internes via le

nerf vague. La mesure la plus précise du réflexe vagal est assurée par son effet sur la fréquence cardiaque. Le

contrôle vagal du coeur induit une variabilité accrue du rythme

cardiaque (VRC) (Park et Thayer, 2014, Scott et Weems, 2014). La

VRC est la variation entre deux battements consécutifs: plus la

variation est élevée, plus l'activité parasympathique est élevée. Une VRC élevée reflète le fait qu'un individu peut s'adapter constamment aux changements micro-environnementaux. Une surcharge de stress induit une diminution de la VRC et les mécanismes d'adaptation sont dépassés. Par

conséquent, la faible VRC est à la fois un marqueur du risque

cardiovasculaire et un biomarqueur du stress (Dutheil et al., 2012;

Boudet et al., 2017). De

manière pratique, la mesure de la VRC est facile, non intrusive et sans

douleur, et assure un suivi continu de l'activité du système nerveux

autonome.

Real-time detection of stress needs continuous monitoring. To assess stress in daily life, we also need portable device. These devices must be non-invasive and pain-free. For these reasons, all historical markers of stress measured in blood, saliva, or urine, are excluded. The need to adapt to external and internal events involve the activation of the autonomous nervous system, which is a balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity (Shaffer et al., 2014). Vagal tone is considered to be a measure of parasympathetic activity which controls the resting state of internal organs via the vagus nerve. The most precise measure of the vagal tone is provided via its effect on heart rate. The vagal control of heart induces an increased heart rate variability (HRV) (Park and Thayer, 2014; Scott and Weems, 2014). HRV is the variation between two consecutive beats: the higher the variation, the higher the parasympathetic activity. A high HRV reflects the fact that an individual can constantly adapt to micro-environmental changes. An overload of stress induces a decrease in HRV and the adaptation mechanisms are exceeded. Therefore, low HRV is both a marker of cardiovascular risk and a biomarker of stress (Dutheil et al., 2012; Boudet et al., 2017). Conveniently, the measurement of HRV is easy, non-intrusive and pain-free, and provides continuous monitoring of the activity of the autonomic nervous system.

Real-time detection of stress needs continuous monitoring. To assess stress in daily life, we also need portable device. These devices must be non-invasive and pain-free. For these reasons, all historical markers of stress measured in blood, saliva, or urine, are excluded. The need to adapt to external and internal events involve the activation of the autonomous nervous system, which is a balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity (Shaffer et al., 2014). Vagal tone is considered to be a measure of parasympathetic activity which controls the resting state of internal organs via the vagus nerve. The most precise measure of the vagal tone is provided via its effect on heart rate. The vagal control of heart induces an increased heart rate variability (HRV) (Park and Thayer, 2014; Scott and Weems, 2014). HRV is the variation between two consecutive beats: the higher the variation, the higher the parasympathetic activity. A high HRV reflects the fact that an individual can constantly adapt to micro-environmental changes. An overload of stress induces a decrease in HRV and the adaptation mechanisms are exceeded. Therefore, low HRV is both a marker of cardiovascular risk and a biomarker of stress (Dutheil et al., 2012; Boudet et al., 2017). Conveniently, the measurement of HRV is easy, non-intrusive and pain-free, and provides continuous monitoring of the activity of the autonomic nervous system.

Measuring Heart Rate Variability

La

manière la plus précise de procéder à la VRC est d'utiliser un

Holter-électrocardiogramme qui est un petit dispositif médical appliqué

sur la poitrine. Un

Holter-électrocardiogramme donne l'heure exacte en millisecondes entre

deux battements consécutifs, sur la base des ondes R (Malik et al.,

1996). Le Holter-électrocardiogramme est coûteux, doit être placé précisément et peut causer de l'inconfort à porter. Par

conséquent, les ceintures d'émission de fréquence cardiaque proposent

maintenant une mesure fiable de VRC (Akintola et al., 2016; Hernando et

al., 2016). En

raison de la quantité importante de données à traiter, VRC nécessite

une analyse hors ligne, qui n'est pas compatible avec l'évaluation en

temps réel du stress. Une

nouvelle méthode de développement, qui utilise la détection de

changements abrupts dans la VRC, permettra d'identifier des événements

stressants (Azzaoui et al., 2014, Dutheil et al., 2015). La fréquence cardiaque, et donc la VRC, sont l'une des mesures physiologiques les plus faciles accessibles au grand public. Une

ceinture émettrice de fréquence cardiaque est une option budgétaire

avec des mesures précises, mais pas aussi pratique et encore plus

intrusive qu'un simple bracelet. Certains capteurs de poignet sont disponibles, mais ils manquent toujours de résolution.

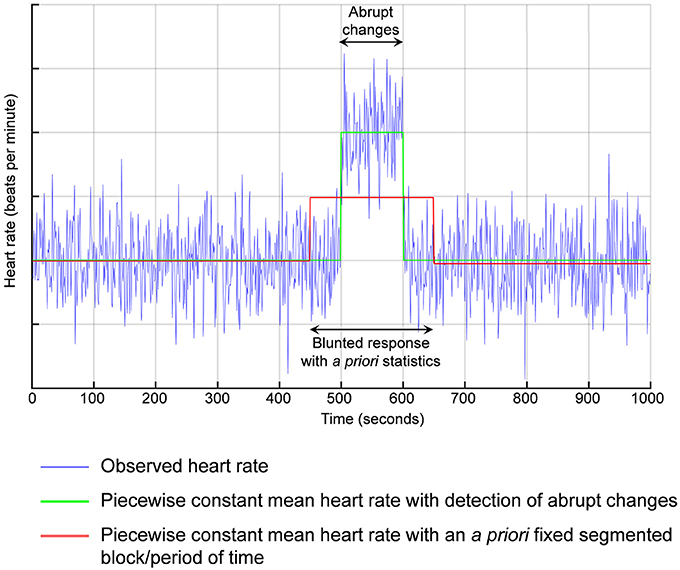

The most accurate way of proceeding HRV is to use a Holter-electrocardiogram which is a small medical device applied on the chest. A Holter-electrocardiogram give the exact time in milliseconds between two consecutive beats, based on R waves (Malik et al., 1996). The Holter-electrocardiogram is expensive, need to be precisely placed, and can cause some discomfort to wear. Therefore, heart rate transmitter belts now propose reliable measure of HRV (Akintola et al., 2016; Hernando et al., 2016). Due to the important amount of data to be processed, HRV require offline analysis witch is not compatible with real-time evaluation of stress. New method in development, that use detection of abrupt changes in HRV, will allow the identification of stressful events (Azzaoui et al., 2014; Dutheil et al., 2015). Heart rate, and thus HRV, are one of the easiest physiological measurements accessible to the general public. A heart rate transmitter belt is a budget option with accurate measures, but not as practical as and still more obtrusive than a simple wrist-band. Some wrist-based sensors are available but still lack of resolution to be used.

The most accurate way of proceeding HRV is to use a Holter-electrocardiogram which is a small medical device applied on the chest. A Holter-electrocardiogram give the exact time in milliseconds between two consecutive beats, based on R waves (Malik et al., 1996). The Holter-electrocardiogram is expensive, need to be precisely placed, and can cause some discomfort to wear. Therefore, heart rate transmitter belts now propose reliable measure of HRV (Akintola et al., 2016; Hernando et al., 2016). Due to the important amount of data to be processed, HRV require offline analysis witch is not compatible with real-time evaluation of stress. New method in development, that use detection of abrupt changes in HRV, will allow the identification of stressful events (Azzaoui et al., 2014; Dutheil et al., 2015). Heart rate, and thus HRV, are one of the easiest physiological measurements accessible to the general public. A heart rate transmitter belt is a budget option with accurate measures, but not as practical as and still more obtrusive than a simple wrist-band. Some wrist-based sensors are available but still lack of resolution to be used.

The Detection of Abrupt Changes

La

littérature antérieure a rapporté une VRC de référence normale ou

altérée chez les

personnes avec un diagnotic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme

(Cheshire, 2012; Kushki et al., 2014). De

même, même si les

personnes avec un diagnotic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme et les contrôles sans

autisme peuvent partager un modèle similaire de modifications autonomes suite à

un stress mental aigu (Kushki et al., 2014), certains auteurs ont

également signalé une réponse à la VFC émoussée à un stress aigu

(Hollocks et al., 2014 , 2016). Bien que les réponses soient encore liées au stress, les méthodes d'analyse de la réponse VRC sont discutables. L'enregistrement

par électrocardiogramme est habituellement segmenté en blocs a priori

de 5 min chacune ou autre période de temps fixe a priori. Notre méthode de changement de point est statistiquement différente. Nous

détectons le changement brutal, puis on calcule la valeur moyenne de

VRC entre deux changements abrupts consécutifs (figure 1). La

détection de changements abrupts est une approche statistique basée sur

une base individuelle et non sur un niveau normalisé de population. Il n'y a pas besoin d'un groupe témoin. Les statistiques personnalisées sont calculées dans les séries chronologiques de chaque individu, ce qui exclut les biais. La

détection de changements abrupts a une courte histoire en médecine,

mais une longue histoire en finance quantitative, qui a conduit à

plusieurs prix Nobel (Mandelbrot, 1963; Engle et Granger, 1982; Hansen,

1982; Granger, 2004).

Previous literature have reported either normal or impaired baseline HRV in people with autism spectrum disorder (Cheshire, 2012; Kushki et al., 2014). Similarly, even if people with autism and healthy controls may share similar pattern of autonomic modifications following an acute mental stress (Kushki et al., 2014), some authors also reported a blunted HRV response to an acute stress (Hollocks et al., 2014, 2016). Despite the responses were still linked with stress, methods to analyze HRV response are questionable. Electrocardiogram recording are typically segmented into a priori blocks of 5 min each or other a priori fixed period of time. Our change point method is statistically different. We detect the abrupt change, then we calculate the mean value of HRV between two consecutive abrupt changes (Figure 1). The detection of abrupt changes is a statistical approach based on an individual basis and not on a population normalized level. There is no need for a control group. Personalized statistics are computed within the time-series of each individual, precluding bias. Detection of abrupt changes has a short history in medicine but a long history in quantitative finance, which has led to several Nobel prizes (Mandelbrot, 1963; Engle and Granger, 1982; Hansen, 1982; Granger, 2004).

Previous literature have reported either normal or impaired baseline HRV in people with autism spectrum disorder (Cheshire, 2012; Kushki et al., 2014). Similarly, even if people with autism and healthy controls may share similar pattern of autonomic modifications following an acute mental stress (Kushki et al., 2014), some authors also reported a blunted HRV response to an acute stress (Hollocks et al., 2014, 2016). Despite the responses were still linked with stress, methods to analyze HRV response are questionable. Electrocardiogram recording are typically segmented into a priori blocks of 5 min each or other a priori fixed period of time. Our change point method is statistically different. We detect the abrupt change, then we calculate the mean value of HRV between two consecutive abrupt changes (Figure 1). The detection of abrupt changes is a statistical approach based on an individual basis and not on a population normalized level. There is no need for a control group. Personalized statistics are computed within the time-series of each individual, precluding bias. Detection of abrupt changes has a short history in medicine but a long history in quantitative finance, which has led to several Nobel prizes (Mandelbrot, 1963; Engle and Granger, 1982; Hansen, 1982; Granger, 2004).

FIGURE 1

Figure 1. Detection of abrupt changes. For example, if the response in heart rate is delayed from the acute stress, previous methods using a priori segmented periods of time would average between the basal values and the stress reaction leading to a blunted response.

Figure 1. Detection of abrupt changes. For example, if the response in heart rate is delayed from the acute stress, previous methods using a priori segmented periods of time would average between the basal values and the stress reaction leading to a blunted response.Stress Assessment in Daily Life

Cependant,

la plupart des études qui ont évalué la VRC chez lespersonnes avec un diagnostic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme étaient en laboratoire et non dans la vraie vie

quotidienne. Être

dans un laboratoire est une tâche difficile par lui-même pour les

personnes personnes avec un diagnostic de trouble du spectre de l'autisme et peut générer

une hyperréactivité du système nerveux autonome (van Steensel et al.,

2011; Jurko et al., 2016). Le

développement récent de la portabilité des appareils, ainsi que du

traitement des données, donne la possibilité de concevoir de nouveaux

dispositifs qui peuvent être utilisés dans la vie quotidienne pour

effectuer une évaluation du stress (El Kaliouby et al., 2006; Picard,

2009). Bientôt, juste une montre devrait fournir une surveillance fiable de la VRC continue. Ces

montres pourraient facilement être connectées à une application de

smartphone conçue pour la détection en ligne de changements abrupts. Ces

solutions novatrices de traitement des données permettront d'informer

en direct les niveaux de stress aux personnes atteintes d'autisme et à

leurs aidants naturels. En

fin de compte, cette connaissance devrait permettre une intervention

appropriée, en particulier par l'enseignement de l'auto-réponse dans

différents contextes sociaux, limitant ainsi l'émergence de

comportements perturbateurs (Dawson, 2008). Les

possibilités ne sont pas limitées aux troubles du spectre de l'autisme et

de nombreuses conditions ou situations de travail devraient bénéficier

de mesures objectives du stress.

However, most studies which evaluated HRV on individuals with autism were in laboratory and not in real daily life. Being in a laboratory is a challenging task by itself for people with autism spectrum disorder, and can generate hyper-reactivity of the autonomic nervous system (van Steensel et al., 2011; Jurko et al., 2016). Recent development in device portability, as well as data processing, give the opportunity to conceive new devices that can be used in daily life to perform stress assessment (El Kaliouby et al., 2006; Picard, 2009). Soon, just a watch should provide reliable continuous HRV monitoring. These watches could easily be connected to a smartphone application designed for the online detection of abrupt changes. These innovative data processing solutions will allow a live insight of the stress levels to be provided to individuals with autism and to their caregivers. Ultimately, this knowledge should allow appropriate intervention, particularly through the teaching of self-responses in different social contexts, thus limiting the emergence of disruptive behaviors (Dawson, 2008). Possibilities are not limited to autism spectrum disorders and many conditions or working situations should benefit from objective measures of stress.

However, most studies which evaluated HRV on individuals with autism were in laboratory and not in real daily life. Being in a laboratory is a challenging task by itself for people with autism spectrum disorder, and can generate hyper-reactivity of the autonomic nervous system (van Steensel et al., 2011; Jurko et al., 2016). Recent development in device portability, as well as data processing, give the opportunity to conceive new devices that can be used in daily life to perform stress assessment (El Kaliouby et al., 2006; Picard, 2009). Soon, just a watch should provide reliable continuous HRV monitoring. These watches could easily be connected to a smartphone application designed for the online detection of abrupt changes. These innovative data processing solutions will allow a live insight of the stress levels to be provided to individuals with autism and to their caregivers. Ultimately, this knowledge should allow appropriate intervention, particularly through the teaching of self-responses in different social contexts, thus limiting the emergence of disruptive behaviors (Dawson, 2008). Possibilities are not limited to autism spectrum disorders and many conditions or working situations should benefit from objective measures of stress.

Author Contributions

CH, Drafting the article. PC and PRB, Critical revision

of the article. FD, Drafting the article, Final approval of the version

to be published.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in

the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be

construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Akintola, A. A.,

van de Pol, V., Bimmel, D., Maan, A. C., and van Heemst, D. (2016).

Comparative Analysis of the Equivital EQ02 Lifemonitor with Holter

Ambulatory ECG device for continuous measurement of ECG, heart rate, and

heart rate variability: a validation study for precision and accuracy. Front. Physiol. 7:391. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00391

Boudet, G.,

Walther, G., Courteix, D., Obert, P., Lesourd, B., Pereira, B., et al.

(2017). Paradoxical dissociation between heart rate and heart rate

variability following different modalities of exercise in individuals

with metabolic syndrome: The RESOLVE study. Eur. J. Prevent. Cardiol. 24, 281–296. doi: 10.1177/2047487316679523

Dutheil, F.,

Boudet, G., Perrier, C., Lac, G., Ouchchane, L., Chamoux, A., et al.

(2012). JOBSTRESS study: comparison of heart rate variability in

emergency physicians working a 24-hour shift or a 14-hour night shift–a

randomized trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 158, 322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.141

Hollocks, M. J.,

Howlin, P., Papadopoulos, A. S., Khondoker, M., and Simonoff, E. (2014).

Differences in HPA-axis and heart rate responsiveness to psychosocial

stress in children with autism spectrum disorders with and without

co-morbid anxiety. Psychoneuroendocrinology 46, 32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.04.004

Malik, M.,

Bigger, J. T., Camm, A. J., Kleiger, R. E., Malliani, A., Moss, A. J.,

et al. (1996). Heart rate variability: standards of measurement,

physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the

European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing

and Electrophysiology. Circulation 93, 1043–1065. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043

Cédric Hufnagel

Cédric Hufnagel Patrick Chambres

Patrick Chambres Pierre R. Bertrand

Pierre R. Bertrand Frédéric Dutheil

Frédéric Dutheil

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire